Of the 20 or so books I’ve read this year, the one that made the most impression on me from a healing and therapeutic perspective was ‘Adult children of Emotionally immature Parents’ by Lindsay Gibson (2015). (As an added note I’m slowly working my way through her follow up ‘Recovering from Emotionally Immature parents’ (2019))

Her first book was the one in which I ticked, underlined, marked and wrote comments in nearly every page, for me its a good examination of Emotional immaturity, the types of emotionally immature parents and how children react and what children have to do to survive and do to respond to them. What I found most interesting is that children respond, broadly, to emotionally immature parents (there are 4 types she describes) in one of two ways, being an internaliser, and an externaliser. These both existing along a spectrum and changes occurring during stress, after therapy and self realisations.

I realised, quite obviously that I am an internaliser. So, I would like to share with you some of the aspects of the internaliser, because in a way, if you’re an externaliser, you’re probably not going to be interested in reading this blog anyway. Self help, learning and reflection aren’t your bag, most of the time.

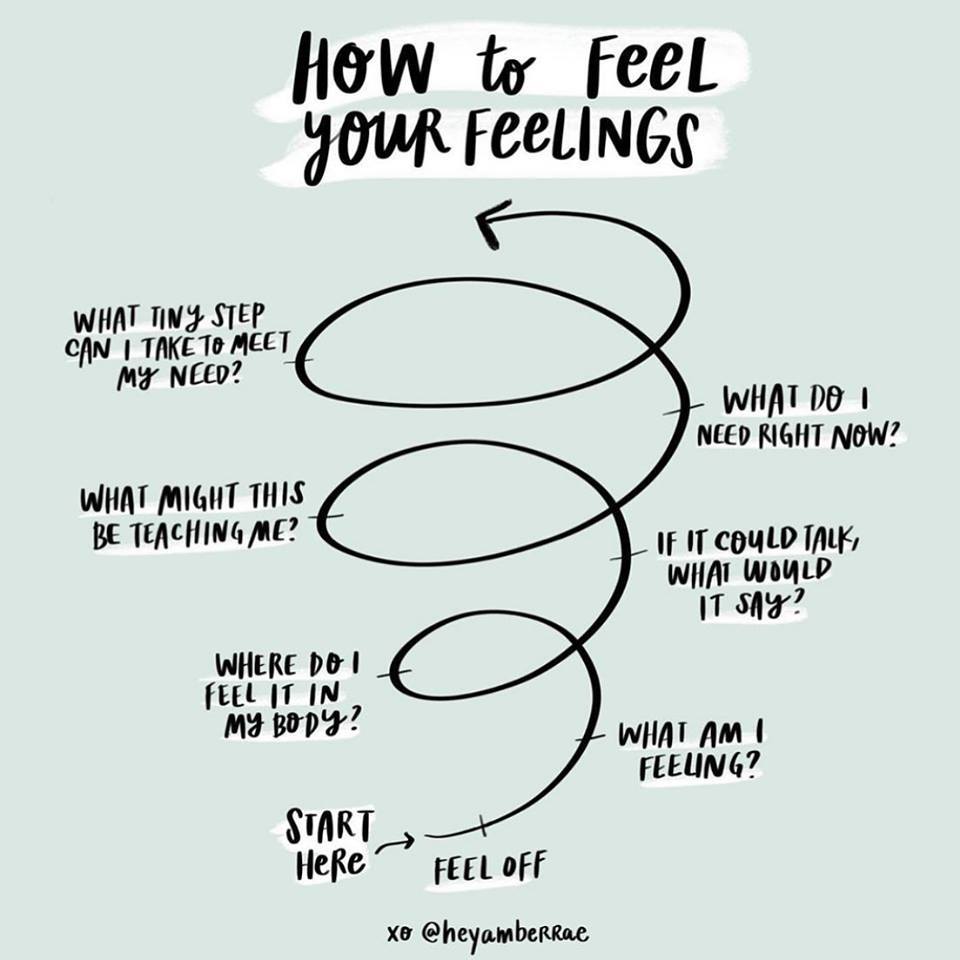

If you are an internaliser like me, then you are like to :

Worry, think that solutions start on the inside, be thoughtful and empathetic, think about what could happen, overestimate difficulties, try and figure out what’s going on (I was very perceptive as a child, some might call that over vigilance) , looking for their role in cause of a problem (‘what did I do?’), engage in self reflection and taking responsibility, figure out problems independently and deal with reality as it is and be willing to change.

I think before I act, as an internaliser, and also believe emotions can be managed, I feel guilty easily and I find the inner psychological world fascinating. (I nearly did a psychology degree aged 18, and recently completed a psychology module for my MA), and in relationships im likely to put other peoples needs first, consider changing myself to improve the situation, request dialogue to sort something out (ah ha.- thats why I like ‘conversation’ as a youth worker..) and want to help others understand why theres a problem.

If you want to know what an externaliser is like, then think about some of the opposites to the above. If you have any experience with someone who acts like an child but in adult form, then that is an externaliser. They deny reality and expect everyone else to sooth them, as they lash out, externalising emotions with little control or sense of consequences. Lindsey’s comment on these is that balance is a key, an extreme internaliser or externaliser is a dangerous thing, only that an extreme externaliser is also a danger to other people, all of the time.

I would say that I was on the middle to extreme internaliser space on the scale. Taking on and feeling guilt, for everything (‘Sorry seems to be the easiest word’), and revolving my sense of self around other people. Realising my co-dependancy tendencies last year was part of this. As Lindsay describes, children adopt one of two principle strategies for coping within such an emotionally immature situation, albeit, everyone in some way is along the spectrum as we can all be described as a mixture of internalisers and internalisers.

But I now know and understand my internalised self. And that is a good thing. I also have a better understanding of its strengths and weaknesses and ill share some of these below. And, I can accept that this is the way I chose to survive, cope and respond in such an emotionally toxic family upbringing.

Being an internaliser means that you are likely to, and I identify many of these:

Being highly sensitive and perceptive; they notice everything

They have strong emotions; they can be seen as ‘too emotional’ , ‘too sensitive’ – that’s because they hold all those emotions and they intensify as they do so

Internalisers have a deep need for connection – they are extremely sensitive to the quality of emotional intimacy in relationships – they want to go deep…

Internalisers have strong instincts for Genuine engagement – ‘it is crucial that internalisers see their instinctive desire for emotional engagement as a positive thing’ (rather than interpret it as needy or desperate)

Forging Emotional connections outside of the family – children who are internalisers are usually adept at finding potential sources of emotional connection outside of the family. They notice when other people provide warmth, seek out relationships with safe people outside the family to gain an increased sense of security. (I know where I felt ‘home’ as a child/teenager) This can also include pets, friends and spirituality. (NB crossover piece on youth work relationships with children of emotionally immature parents..)

Internalisers are often apologetic about needing help they often feel embarrassed or undeserving, and they are often surprised to have their feelings taken seriously. They often downplay their suffering, even wondering if ‘other people’ are more in need of therapy time than they are.

Internalisers become invisible and easy to neglect. Whereas explosive externalisers are easy to spot. Internalisers rely on inner resources and try and solve problems on their own.

Internalisers are overly independent

Internalisers don’t see abuse for what it is – often minimising it as ‘no big deal’

Internalisers do most of the work in relationships – sometimes doing the emotional work for parents, as emotionally immature parents avoid doing responsible emotional work themselves.

However.. they also… Overwork in the adult relationship, often playing both parts of the emotional work in a relationship, they attract needy people (everyone trusts them, being the ‘go-to’ person.) , they can believe that self-neglect can bring love (‘self sacrifice is the greatest ideal’ say parents to internalising children, and associate these with religion…in this way, writes Graham, ‘religious ideas that should be spiritually nourishing are instead used to keep idealistic children focussing on the care of others’

As I read the section on ‘what its like being an internalising adult’ I realised so much about me, about how I reacted in my childhood, my behaviour and what I did to cope, find emotional depth, nurturing and support outside the family home, I see it now, and once I saw it it was freeing to realise. It was also freeing to see how I made decisions based on my past that were almost inevitable without the kind of deep emotional work that I could have undertaken. But as an internaliser I orientated around inner strengths and survival, not seeing abuse for what it so clearly was.

I love my internal sense of self. I know its a good thing, and knowing about it means that I can fine tune it, and see it for its strengths and weaknesses. I know better how to love my internalising self, I think.

In Part 2, ill share more about the strategies for keeping an internalising self healthy…and that is here

References

Graham, Lindsay, 2015, Adult Children on Emotionally Immature Parents

Graham, Lindsay, 2019, Recovering from Emotionally Immature Parents